The preventive role of the judiciary in protecting the financial interest of the European Union.

A comparative analysis for improved performance

47

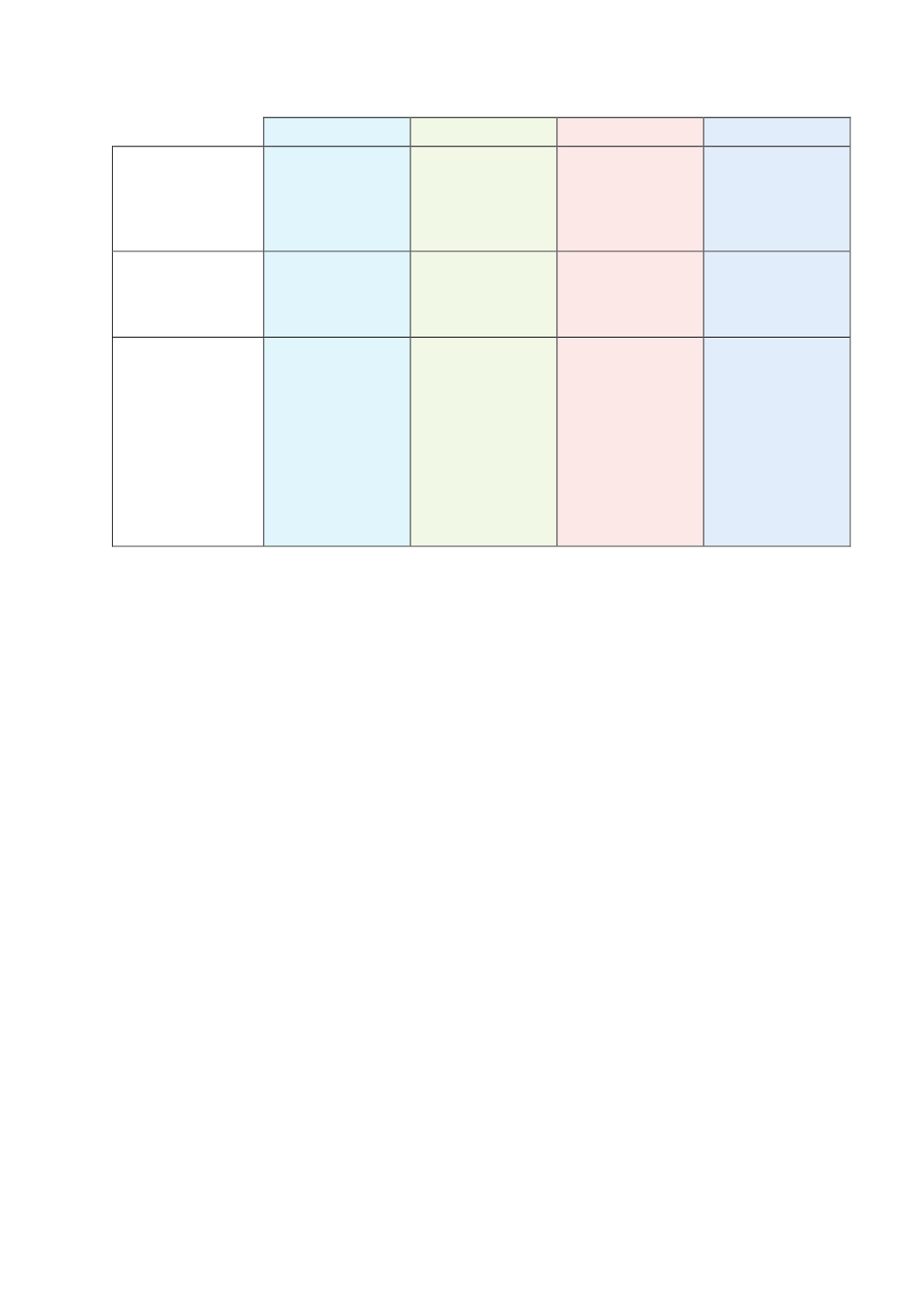

Greece

Italy

Lithuania

Romania

Grounds

for

exclusion from a

tender according to

the

procurement

regulations

Max. 5 years in the

case of mandatory

exclusion grounds

(convictions

for

crimes)

Max. 5 years in the

case of mandatory

exclusion grounds

(convictions

for

crimes)

Max. 5 years in the

case of mandatory

exclusion grounds

(convictions

for

crimes)

Max. 5 years in the

case of exclusion

grounds

including

conviction

for

crimes

Length of the ban

from

public

procurement as a

criminal sanction

NA

A maximum of 2

years

(for

legal

persons)

NA

From 1 year to 3

years

Administrative bans

form

public

procurement

Maximum

of

6

month

NA

3 year for economic

operators on the

“List of Unreliable

Suppliers”

1 year for economic

operators on the

“List of Suppliers

that have Submitted

Fraudulent

Information”

NA

Most of the experts and practitioners interviewed for the present research haven’t identified major risks

in the differences between the periods of exclusions stipulated by different regulations at national and

European level; a more focused analysis is needed. The differences in length and regulation can raise

problems on applying rules on exclusions and banns in international contexts, when economic operators

convicted in one county participate to a tender in another state, within the EU or not.

7.3.

Compliance with the presumption of innocence

While the exclusion form public procurement cannot happen on grounds of unfinished judicial

proceedings in respect of criminal acts, in none of the cases analysed, can such proceedings provide

information to the contracting authorities regarding a serious breach of professional conduct or another

reason for exclusion not requiring a criminal conviction. Therefore, although the blamed deed is not

proved to be a criminal offence and it will not generate a conviction, it can determine an exclusion from

a tender. This is not considered discriminatory, as it is a protectionmeasure for the contracting authorities

and public funds. The problem lies in the lack of a clear definition of a “serious breach of professional

conduct”.

Experts recognise this is a challenging situation from the point of view of the presumption of innocence

principle. However, they underlined that in these situations, until a final conviction, bidders have the

possibility to prove they took remedial measures within their organisations and be allowed to participate

in the tender. On the other hand, self-cleaning regulations and defences available are also vague and

open to interpretation and subjectivity, and, therefore, the contracting authorities can be unfair, failing

to observe the principle of transparency and equal treatment, and clear provisions are needed.